Basement moisture refers to liquid water or elevated humidity present within a below-grade space that reaches materials through seepage, condensation, or vapor drive, and it undermines building durability, energy performance, and occupant health.

Understanding the primary pathways—groundwater/hydrostatic pressure, capillary action, foundation cracks, and warm-air condensation—lets homeowners diagnose problems early and prioritize fixes that reduce wood rot, insulation failure, and poor indoor air quality.

This article explains how moisture interacts with wood framing and insulation at a material level, shows measurable thresholds to watch (for example, sustained relative humidity above 60%), and outlines stepwise interventions to stop damage and restore comfort.

You will learn the common causes and visible signs, how moisture accelerates wood decay and structural weakening, which insulation types fail or resist moisture, how damp basements affect air quality and respiratory risk, and practical exterior and interior remediation strategies.

The guidance that follows combines diagnostic checks, simple homeowner actions, and decision points for when more advanced measures — such as drainage retrofit or structural repair — are required to protect the building envelope and indoor comfort.

What Are the Common Causes and Signs of Basement Moisture?

Basement moisture arises when external water or interior vapor reaches below-grade materials through mechanisms like hydrostatic pressure, gutter overflow, or vapor diffusion, producing consequences such as damp surfaces, elevated humidity, and accelerated material decay. The most common causes include groundwater pressure acting on foundation walls, poor surface grading and clogged gutters, plumbing leaks, condensation from temperature differentials, and vapor drive through porous concrete. Detectable signs range from visible efflorescence and damp staining to musty odors and persistent condensation on windows or pipes. Monitoring relative humidity with a hygrometer and checking moisture meter readings on walls and framing helps quantify risk; sustained basement RH above about 60% typically favors biological growth and should trigger corrective action.

Basement moisture arises when external water or interior vapor reaches below-grade materials through mechanisms like hydrostatic pressure, gutter overflow, or vapor diffusion, producing consequences such as damp surfaces, elevated humidity, and accelerated material decay. The most common causes include groundwater pressure acting on foundation walls, poor surface grading and clogged gutters, plumbing leaks, condensation from temperature differentials, and vapor drive through porous concrete. Detectable signs range from visible efflorescence and damp staining to musty odors and persistent condensation on windows or pipes. Monitoring relative humidity with a hygrometer and checking moisture meter readings on walls and framing helps quantify risk; sustained basement RH above about 60% typically favors biological growth and should trigger corrective action.

How Does Condensation and Water Seepage Occur in Basements?

Condensation occurs when warm, moisture-laden indoor air contacts cooler basement surfaces, causing vapor to change to liquid on walls, floors, or pipes; seepage occurs when liquid water enters through cracks, joints, or porous masonry driven by hydrostatic pressure or capillary rise. These mechanisms operate differently: condensation is driven by temperature differentials and ventilation patterns, while seepage involves physical water movement under pressure or along pore networks. Simple homeowner checks include inspecting conditions after heavy rain for new seepage, taping a sheet of plastic to a wall to test for vapor drive, and observing whether moisture forms on the same surfaces during warm periods. Addressing condensation often begins with reducing indoor humidity and improving airflow, whereas seepage commonly requires drainage, grading, or crack repair to eliminate the water source.

What Are the Early Signs of Moisture Damage in Basements?

Early signs of moisture damage include visible staining, salt deposits (efflorescence), peeling or blistering paint, persistent musty odors, and tactile indicators such as spongy or discolored wood; these cues identify both active leaks and chronic damp conditions. Instrument-based signs include elevated readings on a handheld moisture meter in walls or framing and hygrometer readings consistently above recommended basement targets (generally below 50–60% RH). Homeowners should document locations, photograph damage, and perform quick follow-ups like increasing ventilation or running a dehumidifier while monitoring change over several days. If soft or crumbling wood, widespread staining, or fungal growth are detected, prioritize measurement and limit occupant exposure until the moisture source is controlled and affected materials are assessed for remediation.

Basement moisture causes and early indicators lead directly into understanding how persistent wetting undermines structural members and accelerates decay, which is the next critical area to evaluate.

How Does Basement Moisture Damage Wood Framing and Structural Integrity?

Basement moisture damages wood framing by raising wood moisture content above thresholds that enable fungal decay, causing soft rot, strength loss, and dimensional changes that reduce load capacity and distort framing geometry. When wood’s equilibrium moisture content exceeds roughly 20% for extended periods, decay fungi can colonize cellulose and lignin, reducing shear and bending strength; fastener corrosion and insect attraction often compound the problem. The typical progression begins with surface staining and softening, advances to visible decay and loss of cross-section in joists or sill plates, and can lead to sagging floors, sticking doors, or cracked finishes above. Regular inspection for early soft spots, probing suspect areas, and using moisture meters to map high-risk members helps prioritize repairs before irreversible structural compromise occurs. Recognizing how moisture penetrates framing points to targeted remedies—drying, replacing compromised timbers, or eliminating the moisture source—that restore capacity and prolong service life.

Research further elaborates on the specific moisture conditions required for fungal growth and decay in wood.

Wood Moisture Thresholds for Fungal Decay

The aim of cell wall modification is to keep wood moisture content (MC) below favorable conditions for decay organisms. The present paper contributes to this topic and reports on physiological threshold values for wood decay fungi with respect to modified wood. Threshold values for fungal growth and decay (ML≥2%) were determined.

Critical moisture conditions for fungal decay of modified wood by basidiomycetes as detected by pile tests, A Treu, 2016

What Is Wood Rot and How Does Moisture Accelerate Decay?

Wood rot refers to the biological breakdown of wood fibers by decay fungi that consume cellulose and lignin when moisture and oxygen conditions permit, producing weakened, discolored, and crumbly material. Moisture accelerates decay by sustaining the fungal lifecycle: spores germinate and mycelium advance when wood moisture content and ambient humidity exceed thresholds (often >20% wood moisture content and RH >60%), while warm temperatures and poor ventilation speed colonization. Sapwood is typically more vulnerable than heartwood because it contains more accessible nutrients for fungi, and different decay types (brown rot, white rot) produce characteristic textures and strength losses. Early remedial steps include drying the wood (using dehumidification and ventilation), removing irreparably decayed sections, and applying appropriate preservative or repair strategies to restore integrity and prevent recurrence.

How Does Moisture Affect Joists, Beams, and Sill Plates?

Moisture undermines joists, beams, and sill plates by causing section loss from rot, fastener failures from corrosion, and geometric changes such as cupping or sagging that alter load paths and cause visible deflection. Sill plates at the foundation interface are particularly exposed to capillary and seepage-driven moisture and often show the earliest signs of degradation, which can transfer settlement or misalignment into the superstructure above. Inspection techniques include probing suspect members with an awl, measuring midspan deflection of joists relative to adjacent spans, and checking for rusted connectors or displaced framing. Repair options range from temporary shoring and sistering new lumber to full replacement of sill plates and localized beam repairs with engineered solutions; selecting an approach depends on the extent of decay, loads affected, and the underlying moisture control measures implemented to prevent recurrence.

The unique vulnerability of sill plates to moisture transfer and subsequent decay has been a subject of specific research.

Moisture Transfer & Decay in Sill Plates

Although the sill plate is protected from mold and decay by various means, moisture transfer through simulated foundation walls to sill plates is investigated.

Experimental investigation of moisture transfer between concrete foundation and sill plate, F Tariku, 2016

The ways moisture weakens wood framing underscore why selecting appropriate insulation and moisture-management strategies in basements is essential to both energy efficiency and structural preservation.

In What Ways Does Moisture Compromise Basement Insulation Performance?

Basement moisture compromises insulation by collapsing trapped-air pockets that provide thermal resistance, reducing effective R-value, and by creating conditions for mold growth that damage insulation fibers and degrade long-term performance. Wet insulation can conduct heat more readily, create convective loops, and produce thermal bridging around saturated cavities, resulting in increased HVAC runtime and uncomfortable cold surfaces in occupied spaces. Choosing moisture-resistant insulation, installing continuous vapor control on the warm side, and ensuring proper drainage and air sealing preserve both R-value and indoor comfort. Comparing common insulation types clarifies trade-offs between cost, moisture tolerance, and suitability for below-grade use; this comparison helps homeowners select options that maintain energy efficiency and avoid replacement costs.

Different insulation materials perform differently when exposed to moisture:

| Insulation Type | Moisture Resistance | R-value Loss When Wet | Mold Susceptibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiberglass batt | Low — absorbs water into glass fiber and facing | High — loses much of trapped-air performance | High — paper facing and fiber media support mold |

| Cellulose | Low — hygroscopic, retains moisture | High — compacts and loses loft | High — organic fibers promote mold if wet |

| Rigid foam board (XPS/PIR) | Medium-High — resists bulk water, some types absorb little | Low-Moderate — retains much R if closed-cell | Low — closed-cell boards resist microbial growth |

| Closed-cell spray foam | High — low permeability, repels bulk water | Low — maintains R-value when damp | Very low — not a substrate for mold when cured |

This table shows why closed-cell products and rigid foam are preferred for continuous insulation in basements, while batts and cellulose require robust moisture control to remain effective. Selecting materials that match the moisture risk reduces long-term energy loss and maintenance.

How Does Moisture Reduce Insulation R-Value and Energy Efficiency?

Moisture reduces insulation R-value by displacing or compressing trapped air, creating conductive paths through wetted fibers or boards, and enabling convective heat transfer where cavities become partially flooded or ventilated by moist air. For example, wetted fiberglass can lose a substantial fraction of its thermal resistance as air pockets collapse and moisture bridges between fibers; this increases heat flux and forces HVAC systems to run longer to maintain indoor setpoints. Practically, the result is colder basement surfaces, elevated energy bills, and a greater likelihood of condensation on cooler finishes. Addressing these effects involves restoring dryness, improving air sealing, and selecting insulation materials with lower moisture sensitivity for below-grade applications.

What Types of Insulation Are Most Susceptible to Mold Growth?

Insulation types most susceptible to mold growth include organic or fiber-based materials with paper facings — notably cellulose and faced fiberglass batts — because they retain moisture and provide nutrients for fungal colonization. Closed-cell spray foam and many rigid foam boards offer greater resistance because they limit moisture penetration and lack organic substrates that support mold; however, improper installation that traps moisture can still create problems behind vapor-impermeable layers. When determining whether to replace or dry and salvage insulation, consider exposure duration, visible staining or mold, and odor; short-term wetting with rapid drying may allow salvage, while prolonged saturation and biological growth generally warrant replacement to protect indoor air quality.

The insulation discussion naturally connects to how basement moisture affects occupant health and perceived comfort, which is explored next.

How Does Basement Moisture Impact Indoor Comfort and Health?

Basement moisture degrades indoor comfort by creating cold, clammy surfaces, raising humidity that makes spaces feel uncomfortable, and enabling mold growth that emits spores and microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) which reduce perceived air quality. These biological and physical effects can increase symptom prevalence in sensitive occupants—wheeze, nasal irritation, and allergic responses—and contribute to exacerbation of asthma in susceptible individuals. Moisture-driven contaminants can migrate upward through the stack effect or via mechanical systems, spreading spores into living areas above and undermining whole-house indoor air quality. Maintaining basement relative humidity below about 50–60% and controlling water intrusion are key control points to preserve comfort and reduce health risks from biological growth.

What Are the Effects of Mold, Mildew, and Musty Odors on Air Quality?

Mold and mildew release spores, fragments, and mVOCs into indoor air that increase particulate loads and can trigger sensory irritation and allergic reactions in occupants, especially those with preexisting respiratory conditions. Musty odors are a perceptible indicator of microbial metabolism and often correlate with hidden growth behind insulation, wall finishes, or stored items; such odors frequently prompt occupant complaints even when visible growth is limited. Rapid mitigation steps include isolating the area, increasing ventilation if outdoor conditions permit, and using dehumidification to lower ambient RH while investigating sources. Professional remediation becomes necessary when growth is extensive, when sensitive occupants are affected, or when structural materials require removal to stop recurrent contamination.

How Do Basement Humidity Levels Influence Respiratory Health and Allergies?

Basement humidity directly influences biological growth: relative humidity above roughly 60% favors mold and dust mite proliferation, while very low humidity increases irritation and static but is uncommon in basements. Targeting a basement RH under 50–60% year-round minimizes conditions for common allergens and limits condensate formation on cool surfaces. Practical control measures include continuous dehumidification sized to the space, improving ventilation to reduce indoor moisture generation, and sealing bulk water entry points to stop chronic saturation. Regular monitoring with a calibrated hygrometer and seasonal adjustments—higher dehumidification in warm months and balancing with HVAC operation in winter—help maintain the recommended RH window for health and comfort.

Understanding the health and comfort impacts points to a set of prioritized, practical solutions homeowners can apply to prevent and remediate basement moisture problems.

What Effective Solutions Prevent and Remediate Basement Moisture Problems?

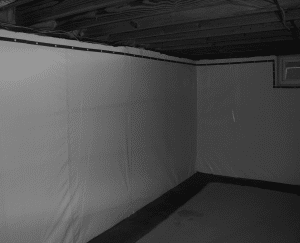

Effective solutions combine exterior measures that stop water from reaching foundation walls with interior systems that remove or control residual moisture, yielding a layered defense that protects structure, insulation, and indoor air quality. Exterior priorities include grading to shed water away, functional gutters and downspouts that move runoff well clear of the foundation, and sub-slab or perimeter drainage systems (French drains) that relieve hydrostatic pressure. Interior measures focus on capturing and removing infiltrating water with interior drainage channels and sump pumps, controlling humidity with properly sized dehumidifiers, and selecting moisture-tolerant insulation and continuous vapor control. Together these measures interrupt the primary moisture pathways, stabilize indoor RH, and minimize conditions that cause wood rot and insulation failure. Below is a practical, prioritized how-to checklist to implement key controls.

Effective solutions combine exterior measures that stop water from reaching foundation walls with interior systems that remove or control residual moisture, yielding a layered defense that protects structure, insulation, and indoor air quality. Exterior priorities include grading to shed water away, functional gutters and downspouts that move runoff well clear of the foundation, and sub-slab or perimeter drainage systems (French drains) that relieve hydrostatic pressure. Interior measures focus on capturing and removing infiltrating water with interior drainage channels and sump pumps, controlling humidity with properly sized dehumidifiers, and selecting moisture-tolerant insulation and continuous vapor control. Together these measures interrupt the primary moisture pathways, stabilize indoor RH, and minimize conditions that cause wood rot and insulation failure. Below is a practical, prioritized how-to checklist to implement key controls.

Comprehensive approaches to maintaining dry basements and controlling moisture are well-documented in building science literature.

Strategies for Dry Basements & Moisture Control

Other strategies include the construction of dry basements and crawl spaces, the venting of space heaters directly to the exterior, the removal of unvented kerosene space heaters, and

Moisture control handbook: principles and practices for residential and small commercial buildings, 1996

A stepwise remedial checklist homeowners can follow:

- Correct Surface Drainage: Ensure ground slopes away from the foundation and clear gutters and downspouts so runoff does not pool near the basement perimeter.

- Relieve Hydrostatic Pressure: Install or repair perimeter drains and ensure a functioning sump pump to capture sub-slab or wall seepage.

- Control Interior Humidity: Use a continuous dehumidifier sized for basement volume and monitor RH to keep levels below 50–60%.

- Choose Moisture-Resistant Insulation: Apply closed-cell spray foam or continuous rigid foam on walls and avoid wettabled batts in high-risk areas.

- Repair Penetrations and Cracks: Seal foundation cracks and service penetrations to reduce vapor and liquid intrusion.

Implementing these steps reduces moisture inputs and improves indoor comfort while minimizing conditions for future decay and biological growth. Prioritizing actions depends on whether moisture is episodic (e.g., after storms) or chronic (e.g., from high groundwater), and assessing the cause guides whether exterior or interior measures should come first.

Below is a comparison of common solutions showing relative cost, efficacy, and maintenance considerations to aid decision-making:

| Solution | Typical Impact | Maintenance Needs |

|---|---|---|

| Exterior grading & gutters | High — prevents most runoff-driven infiltration | Moderate — seasonal gutter cleaning |

| French drain / exterior membrane | High — addresses hydrostatic pressure at source | Low-Moderate — occasional inspection |

| Interior drainage + sump pump | High — effective for active seepage | Moderate — test pump, maintain battery backup |

| Continuous dehumidifier | Medium-High — controls RH, prevents condensation | High — regular filter and condensate management |

| Closed-cell spray foam insulation | Medium — creates vapor barrier and insulation | Low — initial cost, minimal upkeep |

This table clarifies trade-offs: exterior fixes often provide the most durable prevention, while interior systems manage residual water and humidity; combining approaches yields the most reliable results.

When moisture problems are persistent or involve structural wood damage, extensive mold, or complicated drainage, consult a structural engineer or certified remediation professional to evaluate underlying causes and design repairs. For routine issues, homeowners can often implement grading improvements, gutter repair, and dehumidification themselves, but large-scale drainage retrofits or significant wood replacement require experienced contractors.

The practical solutions above close the loop from diagnosis to prevention and remediation, ensuring that moisture controls protect framing, preserve insulation performance, and restore healthy, comfortable indoor conditions.

A.M. Shield Waterproofing recently awarded the Basement Health Association STAR Award for exceptional customer care for the fifth year in a row. Servicing Long Island, NYC and Westchester with Nationally Certified Waterproofing and Mold Remediation Specialists they are able to provide the highest level of professional solutions. A.M. Shield has the widest range of services available to property owners in the greater New York area utilizing multiple techniques in exterior foundation waterproofing, interior drainage, foundation crack injections and foundation repair solutions,. A.M. Shield™s environmental division will assess the damage, repair the problem and create a healthy environment for property owners who experience mold or moisture problems.